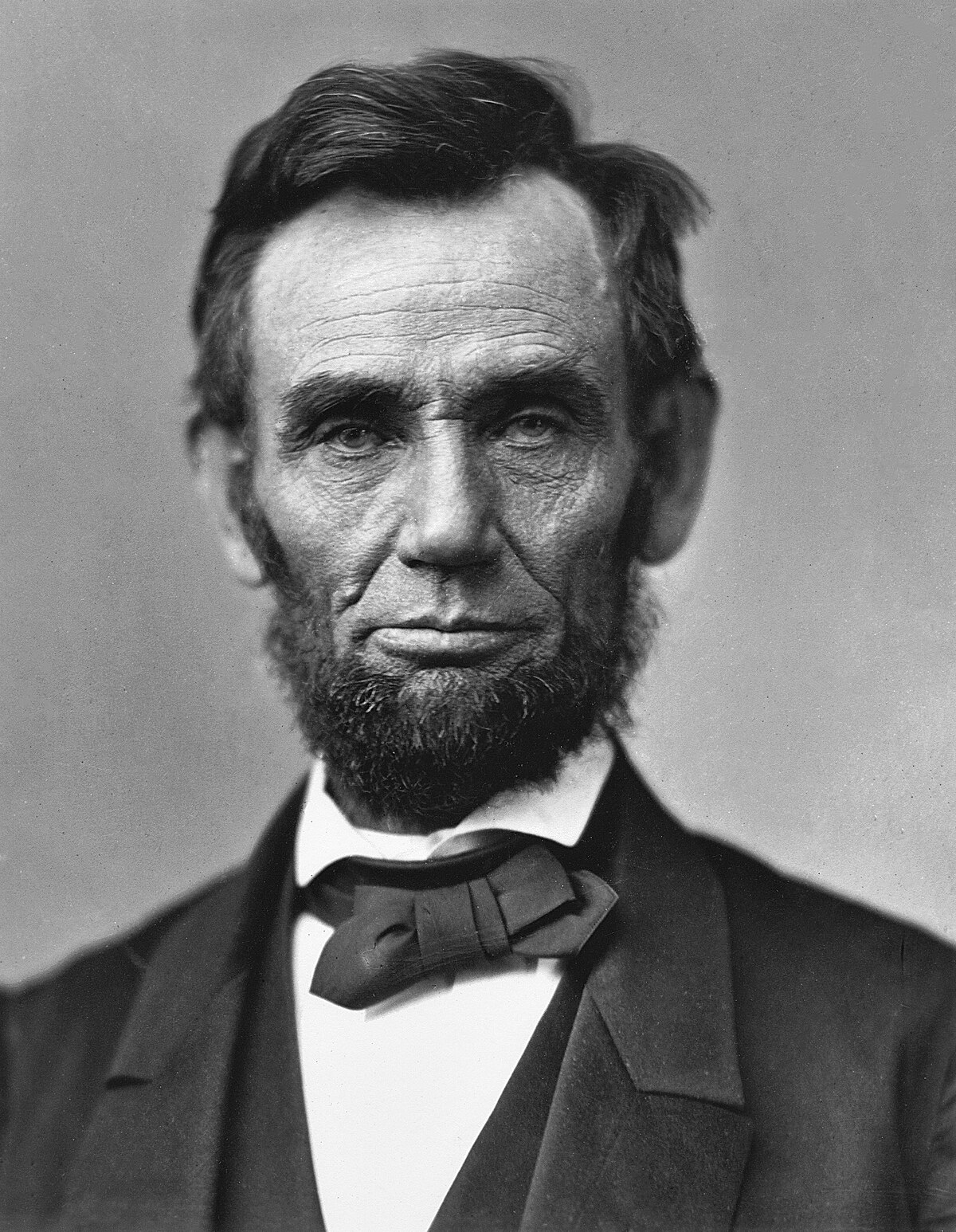

President Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgivings a national holiday in 1863.

President Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgivings a national holiday in 1863.

In 1619 in Virginia, and in 1621, when colonists in Plymouth, Massachusetts, later known as the Pilgrims HELD A 3-DAY FEAST RECOGNIZING A SUCCESSFUL HARVEST.

The newly settled Europeans did not invite the Natives to their feast. They had a second feast in honor of the help the Pilgrims received from the Natives in cultivating crops and surviving their first harsh winter and it lasted three days. The Natives invited themselves.

Chief Ousamequin, leader of the Wampanoag Tribe, had declared an alliance with the settlers, and members of the tribe were showing up to honor a mutual-defense pact; they’d heard the Pilgrims shooting their guns in celebration and thought they were in combat. After some talk, they decided to spend three days together and join the feast—but this type of coming together did not become a warm, fuzzy tradition as you may have been taught in school.

Later, US Presidents including George Washington, John Adams, and James Madison called for days of thanks throughout their presidencies.

It was not until 1863, during the Civil War, that President Abraham Lincoln declared a national Thanksgiving Day to be celebrated by the country each November.

The Original Settlers

The Wampanoag Nation was native to all of Southeastern Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island, encompassing over 67 distinct tribal communities which included tribes such as the Natick, Pokanoket, Nantucket, Chappaquiddick, Patuxet, and Massachusett.

The Wampanoag Nation was native to all of Southeastern Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island, encompassing over 67 distinct tribal communities which included tribes such as the Natick, Pokanoket, Nantucket, Chappaquiddick, Patuxet, and Massachusett.

In the 1600s, there were as many as 40,000 people in the 67 villages that made up the Wampanoag People, who first lived nomadic hunting and gathering culture.

These villages covered the territory along the east coast. Their people had been living on this part of Turtle Island for more than 12,000 years. The Wampanoag, like many other Native People, often refers to the earth as Turtle Island.

Skilled hunters, gatherers, farmers, and fishers during spring and summer, the Wampanoag moved inland to more protected shelter during the colder months of the year. The Wampanoag had a reciprocal relationship with nature and believed that as long as they gave thanks to the bountiful world, it would give back to them.

By about 1000 AD, archaeologists have found the first signs of agriculture, in particular the corn crop, which became an important staple, as did beans and squash.

The Wampanoag tribe was known for its beadwork, wood carvings, and baskets. Wampanoag artists were especially famous for crafting wampum out of

The Wampanoag tribe was known for its beadwork, wood carvings, and baskets. Wampanoag artists were especially famous for crafting wampum out of  white and purple shell beads.

white and purple shell beads.

Wampanoag people befriended the pilgrims at Plymouth Rock and brought them corn and turkey for their survival. Unfortunately, the relationship went

downhill from there, and disease and British attacks killed most of the Wampanoag people. The surviving Wampanoags are still living in New England today.

The Wampanoag have lived in southeastern Massachusetts for more than 12,000 years. They are the tribe’s first encountered by Mayflower Pilgrims when they landed in Provincetown Harbor and explored the eastern coast of Cape Cod and when they continued on to Patuxet (Plymouth) to establish Plymouth Colony.

GENOCIDE

Slavery

In 1614, a European explorer kidnapped twenty Wampanoag men from Patuxet (now Plymouth) and seven more from Nauset on Cape Cod to sell them as slaves in Spain. Only one is known to have returned home: Tisquantum, who came to be known as Squanto. This tragic and compelling backstory to the colonization of Plymouth has been long overlooked and comes to life in the exhibit’s dramatic images and video impact statements.

The slave kidnapping tragedy utilized the communication system between the tribes. The Messenger Runners— members of the Tribe who were chosen, based upon their endurance and their capacity for memory, to run to neighboring villages and territories to deliver essential messages. This message required the runner to cover a distance of 40 miles.

DISEASE

Between 1616 and 1619 Native villages of coastal New England from Maine to Cape Cod were stricken by a catastrophic plague that killed tens of thousands, weakening the Wampanoag nation politically, economically, and militarily.

The European settlers gave the Natives blankets infested with a disease, Small Pox, Leptospirosis, or 7-day fever. It robbed the Natives of their immune system for which they had no cure or treatment.

Before 1492, the Natives lived sparsely and were largely isolated from the rest of the world, meaning they were mostly protected from the threat of foreign illness.

They lacked immunity to the pathogens that would eventually arrive. Europeans were exploring the villages of indigenous people long before the Mayflower arrived, and they spread sickness at a devastating rate.

The disease consumed its victims by rotting them from within and causing their skin to turn yellow and fall off. As a witness conveyed to Thomas Morton, “…the hand of God fell heavily upon them, with such a mortal stroke that they died on heaps as they lay in their houses…” Among the dozens of villages wiped out was Patuxet where Thomas Hunt had kidnapped 20 men in 1614 including Squanto, the only one known to return. He returned in 1619 to find all was lost.

Entire villages were lost and only a fraction of the Wampanoag Nation survived. This meant they were not only threatened by the effects of colonization but vulnerable to rival tribes and struggled to fend off the neighboring Narragansett, who had been less affected by this plague. A year later Patuxet became Plymouth Colony.

Wars

In the winter of 1616-17, an expedition dispatched by Sir Ferdinando Gorges found a region devastated by war and disease, the remaining people so “sorely afflicted with the plague, for that the country was in a manner left void of inhabitants”.

Two years later another Englishman found “ancient plantations” now completely empty with few inhabitants – and those that had survived were suffering.

King Philip’s War, also called Great Narragansett War, (1675–76), in British American colonial history, a war that pitted Native Americans against English settlers and their Indian allies that was one of the bloodiest conflicts (per capita) in U.S. history. Historians since the early 18th century, relying on accounts from the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies, have referred to the conflict as King Philip’s War. Philip (Metacom), sachem (chief) of a Wampanoag band, was a son of Massasoit, who had greeted the first colonists of New England at Plymouth in 1621. However, because of the central role in the conflict played by the Narragansetts, who composed the largest tribe lived in southern New England, some historians refer to the conflict as the Great Narragansett War.

In the years before the Mayflower arrived, the effects of colonization had already taken root.

The arrival of the Mayflower

The Mayflower made a 66-day voyage. The Europeans departed Plymouth, England, on 6 September 1620 and arrived at Cape Cod on 9 November 1620. The Mayflower’s passengers disembarked at a time of great change for the Wampanoag.

The Wampanoag traditionally worked together – a number of groups united. The heads of these groups were called Sachems, with a head Sachem managing this democratic network where women and men worked in unity, both with a voice on tribal matters.

Attacks from neighboring tribes meant they had lost land along the coast, and the extraordinary impact of the Great Dying meant the Wampanoag had to reorganize its structure and Sachems had to join together and build new unions.

Four hundred years ago, this newly organized People watched as yet another ship arrived from the east.

These people were different. The Wampanoag watched as women and children walked from the ship, using the waters to wash themselves. Never before had they seen Europeans engage in such an act.

They watched cautiously as the men of this new ship explored their lands, finding what remained of Patuxet and building homes. They watched them take corn and beans, probably winter provisions, stored for the harsh conditions that were to come.

The Wampanoag People did not react.

Given the horrific nature of the past years, the Wampanoag People were understandably wary of this new group. Months would pass before contact. But in this time, they would have recognized the opportunity for a new alliance to help them survive.

EUROPEAN SETTLERS

In March 1621, an English-speaking Native American named Samoset was visiting the Wampanoag chief Ousamequin, known as Massasoit. He is said to have entered the grounds of this new colony and introduced himself and is said to have asked for a beer.

Samoset had learned English from the fishermen who had frequented the waters off the American coast and talked to these new settlers, establishing a rapport.

He later returned with deer skins to trade. They didn’t trade on this occasion, but they did exchange food.

A few days later, Samoset returned. With him came Tisquantum, whose experience meant his English was much advanced. The Wampanoag put Tisquantum to the test and freed him to help these new Englishmen.

He taught them to plant corn, which became an important crop, as well as where to fish and hunt beaver.

He introduced them to the Wampanoag chief Ousamequin, an important moment in developing relations.

A temporary peace

At the same time as the arrival of these newcomers, the Wampanoag were still wary of the nearby Narragansett tribe, who had not been affected as badly by the disease epidemics and remained a powerful tribe.

Ousamequin would have sensed an opportunity to align themselves with these new colonists from England, to protect his people from the Narragansett.

In 1621, the Narragansett sent the new colony a threat of arrows wrapped up in snakeskin. William Bradford, who was governor of the colony at the time, filled the snakeskin with powder and bullets and sent it back. The Narragansett knew what this message meant and would not attack the colony.

Ousamequin established with the Mayflower passengers a historic peace treaty. The Wampanoag went on to teach them how to hunt, plant crops, and how to get the best of their harvest, saving these people, who would go on to be known as the Pilgrims, from starvation.

This ‘peace’ was not necessarily one the Wampanoag were comfortable with. For a period the two groups’ interests aligned – but in the context of 400 years of history, it is a moment in time.

TIMELINE

- 1614 – 20 Indigenous people were taken as slaves.

- 1616-1619 Disease helped kill the Natives.

- 1619 -European settlers landed in Cape Cod and colonized Patuxet, MA. which became Plymouth Colony.

- 1620 – The arrival of the Mayflower in Cape Cod on Nov. 9, 1620

- 1675-1676 King Philips War

- 1863 – Thanksgiving Day became a national holiday.

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe is one of two federally recognized tribes of Wampanoag people in Massachusetts. Recognized in 2007, they are headquartered in Mashpee on Cape Cod. The other Wampanoag tribe is the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard.

References: Plymouth 400, , ![]() Delish,

Delish,

You know there are no records of Wampanoag or Mashpee in Plymouth colony as a pre colonial tribe, nation or settlement. Where are you getting your information from? You are either making things up or having trouble comprehending the information accurately.